Why Did 50 Cent Get Mad When I Asked Him If He Does Steroids?

But first, what did 50 do to make himself a platinum artist on the day his debut album came out?

#1 The Backstory Is Amazing

The first thing most people ever heard about 50 Cent was that he had been shot nine times. That factoid flew through the culture from ear to ear as rapidly as any piece of news ever has. If we could track the number of times news, or gossip, is repeated, the way we track record sales or TV shows, I bet we’d see that that was a multi-platinum factoid. It was heard by as many people as any massive hit record.

You had to be curious about a guy who survived getting shot an absurd number of times. You had to respect his gangster. The story made him seem unkillable and irrepressible and mythical and powerful. It was proof that he had been deep in the streets, but more than that, it was captivating that people hated him so much and wanted him dead so badly that they’d shoot him that many times. The story of 50 Cent began with an amazing story.

That story would grow into the best product launch in the history of hiphop. Most of the time when new artists drop their debut album it takes time for demand to build. But, every once in a while all the stars align and there’s massive demand on day one. 50 Cent’s 2003 debut album Get Rich Or Die Trying sold over 800,000 copies in its first week and another 800,000 copies in its second week. It sold 12 million in its first year, the best-selling album of the year. All this, even though, 50 was an average rapper at best. His rhyming skills were completely forgettable, no one raves about his verses, but he wrote great hooks and had a platinum image—the image he put together on records and in videos and offstage made him incredibly captivating. His brand was former Queens crack dealer and tough street thug who became a rapper. He presented himself as the toughest guy in the industry. 50 himself described it more simply. He told me, “I think kids like me the same way they like the bad guy in a film. People love the bad guy.”

With all of that, 50 created a world where people were clamoring to buy his debut album as soon as it came out. How did he create that? Let me explain. There’s seven major things that went right. This is #1—the backstory.

In hiphop, some rappers’ debut album is preceded by a story. It’s always something pithy and captivating that makes people say ok wow this guy is someone to look out for. Usually, it’s something that confirms how street they are or were. It’s like an elevator pitch telling the culture who they are. Before Reasonable Doubt came out, word swept through hiphop that Jay-Z was coming out soon and he had been a serious street dealer. They said Reasonable Doubt would be his sole album because rap money was too slow for him. This shaped our sense of who he was.

The pre-album story is a crucial part of hiphop marketing. Kanye’s story was one of the best ever—before his first album dropped, word flew around that he had fallen asleep in his car on the way home from the studio, gotten into a car accident, broken his jaw, and, amazingly, went to the studio while his jaw was wired shut to record a song. That spoke to his relentlessness, his will, and his love of music. It told us that he was unstoppable and he was dedicated to making music. It set up his brand.

But no one has ever had a better pre-album story than 50 Cent—“he got shot nine times” said this is someone you need to hear. And the interesting thing is, this part of 50’s rise happened organically. He didn’t tell everyone to tell everyone that story. He wasn’t big enough to push it out back then. He had a traumatic incident that changed his life and when people heard the story, they couldn’t stop talking about it. This is the first thing that really helped made 50 a star and it was organic. It just happened. Most of what happened to make 50 into a day one star was intentional and most of it was planned by him. No one dominates the attention economy like he did without being intentional. But the story of him getting shot nine times caught fire on its own.

#2 Jay-Z Claps Back

Before most of the culture heard that 50 had been shot nine times, some people heard 50’s first record, a funny little 1999 underground single called “How To Rob” in which a rapper describes how he would rob over 40 artists in the industry, saying greasy but funny things about each. For example, he said:

What Jigga just sold, like four milli? He got something to live for

Don't wanna nigga putting four through that Bentley coupe door

I'll manhandle Mariah like "Bitch, get on the ground

You ain't with Tommy no mo', who gon' protect you now?

The lines about Mariah Carey and her ex-husband, Tommy Mottola, then the CEO of Sony Music, definitely got her attention. She was so offended that she demanded 50 change them. He was then on Columbia, a label that was a subsidiary of Sony, so he had to. More importantly, the lines about Jay-Z (Jigga) got his attention at a time when Jay was the hottest rapper in the game and one of the most influential figures in the culture. At that time, if Jay-Z wore something, people bought it. If he said this vodka is good, people bought it. His endorsement was gold. A few months after “How To Rob” dropped, Jay dropped his 4th album Vol 3… The Life and Times of S. Carter, and he shot back at 50 on the song “It’s Hot (Some Like It Hot).” Jay said:

Go against Jigga, yo ass is dense. I’m about a dollar, what the fuck is 50 cents?

Jay-Z mentioned 50, then a largely unknown rapper. This earned 50 a ton of attention and instantly legitimized him. People said, Who’s the guy Jay is clapping back at? Why is Jay talking about him? It told us that 50 was someone who Hov thought was worthy of a response. We knew that Jay would’ve said nothing back to most rappers because he knows his silence is worse than any diss. So responding to 50 was a tacit endorsement from Jay. It helped 50 a lot. The first time I interviewed him he told me, “I don’t know if my career would be where it’s at if he didn’t respond.”

I interviewed 50 three times over the years which turned into its own wild story. That’s down below.

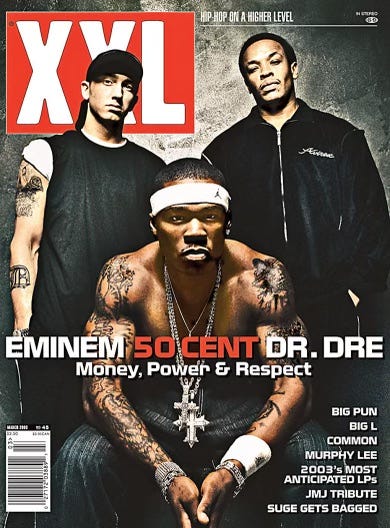

#3 Dre and Em Also Endorse

Breaking new hiphop artists relies on endorsements. Hiphop fans perk up when some major figure they respect tells them that they should check out some new guy. It’s almost a requirement to get some veteran to stand beside you and say you’re an important rapper. It doesn’t always work but when Biggie says yeah, Little Cease is my boy, or when Jay-Z says Memphis Bleek is my boy, that makes us tune in and give them a chance. Better example: when Dr. Dre said Snoop is my boy, we plugged in. Snoop became a legend. When Dre said yo this kid Eminem is amazing, we plugged in. Em became a legend. Then Dre and Eminem signed 50 to their labels. He got a pre-release endorsement from the biggest producer in hiphop, who was also the biggest endorser, and the biggest pop star in hiphop. Then we had interviews where Dre and Em were sitting with 50 talking about how great of an artist he was. That grabbed our attention and heightened our respect for 50. That elevated him even further in the culture.

When Get Rich Or Die Trying came out, the President of Urban Music at Interscope, was Ron Gilyard. I called him to talk about 50’s early days. He said that 50’s early success was not the brainchild of some great manager or some brilliant marketing exec and it definitely wasn’t luck. It was 50. Gilyard said, “He was completely focused on his mission of selling records and everyone around him had to have a role to play in that mission or you were out. He had a ridiculous work ethic. He was determined to outwork everyone. He said yes to every interview, every show, every opportunity to push his name out there. Every day he said, if you’re going to be around me or working for me, if you’re in my orbit, then you’re doing something to push the agenda forward. He was not lazy. There was not one interview he wouldn’t do. There was no place he wouldn’t perform.”

Gilyard said the marketing team wasn’t telling 50 what to do. He was telling them what to do. “If we [at the label] were Florida A&M’s marching band he was the drum major,” Gilyard said. “He was leading the charge. He had the ideas. He had a plan and he led the way. We chose to follow his lead.” Gilyard said 50 was brilliant. “He’s one of the smartest people I’ve ever been around as far as being able to read the culture and market to it. I’ve been around Puff, Jay-Z, Russell, Andre. He was smarter than them at that.” He said 50 used a lot of ideas that he’d learned from being in the streets dealing crack. For example, it was 50’s idea to flood the streets with his mixtapes.

#4 Flood the Streets

When 50 was rising, mixtape culture was an important part of hiphop. Mixtapes were an underground series of collaboration albums where DJs pulled together a slew of MCs, some new, some established, to rhyme over old or new beats. It was a place where MCs could showcase their skills and try different styles or lyrics that they would never do on major label albums. This was stuff for hardcore hiphop fans. The mixtapes weren’t really marketed and usually you didn’t get them in stores. You had to know where to go to get them. Real hiphop fan knew the spots where they could buy mixtapes (which were, by then, on CDs and thus not tapes at all but they were still mixtapes). I used to go to Flatbush and Dekalb in downtown Brooklyn to the guy on the corner and get my Whoo-Kid, my Ron G, my DJ Clue, etc. The mixtape circuit was a crucial way of introducing yourself to the most ardent and discerning hiphop fans. Another artist would’ve jumped on a couple of songs on a mixtape or two and spazzed out to create buzz. 50 overturned the whole system.

50 made a series of album length mixtapes that he gave away for free. No one had ever done that. He wanted to flood the mixtape market with his product and get people used to him and his style so that later on they’d be fans who were willing to buy his debut album because they already knew he was hot. “He gave em free mixtapes,” Gilyard said, “and then you charge them for the actual album and as long as your product can get them to the high that they were chasing, they’ll continue to support you.”

50 told me that when he was a drug dealer in Queens he used to give away product to get people interested in his crack. He brought that same concept with him into the music biz.

He also told me he used to hire guys to rob his rival dealers and then give away their drugs when you bought his in a two for one deal that devalued his rival’s product and made his seem like the best.

“This idea that drug dealers aren’t smart is dumb,” Gilyard said. “Many of them could run corporations better than the people who are currently running them.”

50 was proving that with the way he was running his own project.

#5 The Beef

In hiphop there may be no better marketing tool than beef. When artists begin dissing and threatening each other, it triggers a very basic human instinct to watch. If people start to fight, even if people just argue viciously, others will stop and pay attention. KRS-One launched his career with beef when he attacked MC Shan who was then one of the hottest rappers in the game. 50 wanted to do the same thing. As he moved toward his debut, one of the biggest selling artists in hiphop was Ja Rule. Ja had started out making traditional hiphop but over time he had moved into doing hiphop/R&B collabs where he was rapping and singing alongside Ashanti or J-Lo.

These songs sounded nothing like traditional hiphop as they tried to blend both genres together. They made it look like Ja was lacking the self-seriousness of a drug lord-turned-rapper like 50. Ja was making what we can a call softer, sweeter hiphop that embraced love and joy and welcomed femininity so everything Ja stood for was the opposite of what 50 stood for. He wanted to exploit his opportunity to bully one of the top rappers in the game so, Gilyard said, 50 spent a whole weekend making over 14 records dissing Ja. Among them was a hot record called “Wanksta” that became a major hit before Get Rich came out. At the end of the “Wanksta” video, 50 takes his son’s Ja Rule doll and throws it in the trash.

50 was trolling Ja hard, years before that was a term. This was a smart chess move because it earned 50 attention and it made him seem like a bully which is exactly how he wanted to come across. 50, who was coming with a dark brand of hiphop that came out of his past as a cold-hearted Queens crack dealer, was bullying a huge-selling rapper who was making a kinder, gentler brand of hiphop. For 50 this was a battle that cast him as the savior of hiphop. It was the same sort of posture that Kendrick took against Drake—I’m real hiphop and he’s not. Thus they were saving hiphop from someone who was making hiphop soft. So launching the battle was smart for 50 and the way he prosecuted it was smart, too.

50 understood that he needed to be talked about constantly. He needed to dominate the attention economy. The battle gave him that. But he needed more. He needed a song that would have everyone talking about him.

#6 The Single

“In Da Club” was a hiphop club banger that became pop smash. In 2003 it was just as ubiquitous as “Not Like Us” in 2024, maybe even more. The song made everyone want to dance and it was played everywhere from sweaty little hole in the wall hiphop clubs in Brooklyn to Bat Mitzvahs in Beverly Hills. It has a super poppy beat from Dre but to me the real genius is in the structure. The song starts with a fun, sing-songy hook that’s super easy to remember. “Go shorty, it’s your birthday. We gonna party like it’s your birthday, we gonna sip Bacardi like it’s your birthday, and you know we don’t give a fuck it’s not your birthday.” The repetition of birthday makes these lines fun, bright, and easy to recall. It’s an earworm. Was this a gangsta record from a crack-selling thug? Sure didn’t sound like it was then. Then, right after the hook, just a few seconds into the song, he bangs right into this great, big chorus. “You can find me in the club. Bottle fulla bub, but mommy I got the ex if you into taking drugs. I’m into having sex, I ain’t into makin love, so come give me a hug if you into getting rough.” This is a gangsta love song or a thug’s way of spittin game to a woman. We know he’s hard but this record is funny and kinda sexy, too. A killer combo.

I think it’s really smart to start a song with a chorus. Most songs don’t. Songwriters usually start with a verse and work their way into the chorus. The chorus emerges after the mood of the song has been created. But starting with a verse means the listener has to wait longer to get to the chorus and even longer to their first chance to repeat the chorus. When you start with the chorus you launch into the most ecstatic part of the song right at the top and then about 60 seconds later you come back again with that catchy, ecstatic, captivating, beloved part of the song and, if you’ve done it right, the audience is hooked. Beyonce loves to start with a chorus. “Single Ladies,” “Love On Top,” and “Texas Hold Em” all start with the chorus. Of course, Beyonce didn’t invent this—Bob Marley started with the chorus on “I Shot the Sheriff.” The Beatles did with “She Loves You.” Usher did it with “You Make Me Wanna.” But none of those are debut singles, your first official chance to hook the audience. 50 and Dre understood that the catchiest way to seize the audience’s attention was to start with a chorus.

The category of career debut singles in hiphop is crowded with big records that became iconic. Ol Dirty Bastard set the hiphop world on fire with “Brooklyn Zoo” as did Snoop with “What’s My Name” and Lauryn with “Doo Wop (That Thing)” but those are songs that launched solo careers that came after a successful group career made them household names. There was already attention on them and a deep understanding of who they were.

What 50 had to do was more akin to what Eminem did with “My Name Is” or what Lil Nas X did with “Old Town Road.” Those are introductory records that launched careers. There have been other great, popular debut singles in hiphop—Biggie’s “Juicy,” Pete Rock and CL Smooth’s “They Reminisce Over You,” Outkast’s “Player’s Ball”—but few debut singles have been huge smashes like “In Da Club.” Those songs put a spotlight on their artists but none of them had the spotlight as bright as 50’s because of all the things we’ve discussed and because of the one last thing that propelled 50’s fame and allowed him to dominate the attention economy. A sense that he was, right then, in grave danger.

#7 Danger

The first time I saw 50 I was in the tony West Village of Manhattan where there’s lots of multi-million-dollar homes and upscale restaurants. I was standing outside of a famous photographer’s studio, waiting for 50 to arrive to do the cover shot for the Rolling Stone article I was writing. This lower Manhattan neighborhood could not be any nicer or sweeter but then the hulking GMC truck that carried 50 raced up, screeched to a halt, and all the doors flew open at once as if a head of state was about to get out. A phalanx of giant, dark-suited bodyguards surrounded 50 and the whole group practically ran from the truck to the front door a few yards away. If someone had been there wanting to shoot 50, they wouldn’t have been able to but, again, we were in the West Village. To me it felt like a totally theatrical show of defense in an area where there probably hasn’t been a shooting in decades or a mugging in years. I bet it’s been a while since any crime-level jaywalking happened in the West Village.

But all of that bodyguarding had to happen because we all were being told that 50 was, right then, in grave danger. He had escaped the hood and become a huge star, and for that the streets wanted him dead. They were jealous of his success and they had it out for him. So he had to wear a bullet proof vest all the time and stay flanked by bodyguards. I saw how wearing a vest and needing to be surrounded by guards made him look like a big star. I understood how the idea that people were, right now, trying to kill him made him look like a tough guy. It contributed to the whole story of 50. The thing is, I didn’t buy it.

I spent a few days with him and while we were together I saw him stop on Manhattan street corners and sign autographs and take pictures. This was a man who truly feared for his life?

My 2003 Rolling Stone cover story was titled “The Life Of A Hunted Man.” (I did not choose that.) The subtitle was “At twelve he was a crack dealer. At twenty-three he was nearly shot to death. Now, at twenty-six, he is a hiphop ruler. And old rivals want him dead.” (I didn’t choose that either.) I was asked to write a sidebar for my piece exploring who might be trying to murder him. I politely refused. I just didn’t believe that Ja Rule or someone from the streets of Queens was trying to murder 50. I thought it was a marketing tactic—hey this guy is so badass that people want to kill him. Another great story. Meanwhile, in the face of this danger, 50 seemed to remain calm, further underlining how cool he is. I asked him if he was afraid that he would be killed. He said, “Do I look uneasy to you?” That became a pull-quote. (Didn’t choose that, either.)

Was it marketing? Two decades later, when it might be ok to say, yeah, we played that one up for the cameras, Gilyard still says no. “Whether you believe it or not,” he said, “There was enough data points out there to suggest that taking his safety and his well-being seriously was the right thing to do. There was enough info that he was receiving and that his management was receiving and that the streets was projecting that made it prudent to [protect him].”

So maybe he was being hunted. Whether he was or not, that became another part of the story of 50 Cent, another thing for people to talk about that led to him becoming one of the most commercially successful artists of his time.

50 loved it when we talked about him but he did not love everything that everyone wanted to talk about. Let me break from the story of why his debut was this perfect storm of hiphop marketing and tell you a story that centers 50 but probably says more about me than him. The interview we did for Rolling Stone was the first time I interviewed him. That was when he was first blowing up in 2003. I spent several days with him and I noticed how large he was—he had huge arms and shoulders. I wrote about that but from the context of, here’s someone whose massive body is part of his cultural appeal. Most of the MCs we’d ever seen at that point were thin or average-sized guys. You had some athletic-looking guys like LL, but most rappers did not wow with their bodies. 50 was something new. But because the baseball steroids scandal had not happened, and because steroids were not yet a widely discussed thing, it never occurred to me that it’s very, very hard to get as big as he was without the help of steroids.

In 2005, Jose Canseco’s book Juiced came out and several top baseball players were called before Congress to talk about steroids in baseball. The next year the popular book Game Of Shadows explained how Barry Bonds had acquired and used steroids and a major investigation of steroids in baseball was conducted by a former US Senator. Through all of this, many Americans got a crash course in what steroids did and how they could help you get huge. That’s when I thought oh, 50 Cent has to be doing steroids. Just look at him.

In 2007 I was working at BET—I hosted an entertainment news show called “The Black Carpet”—and I got another chance to interview 50. I said I’ve gotta ask him if he uses steroids. Now, the thing is, it’s illegal and arguably immoral to use steroids if you’re a professional athlete. It’s considered cheating. And it’s dangerous to use steroids if you’re a teenager—in a growing body they can cause intense depression that has, in several cases, led to suicide. But if you’re not a pro athlete and you’re not a teenager, there’s nothing wrong with using steroids. There was a stigma to it but that’s because most of the time when we talked about steroids, it was a pro athlete apologizing for using it. If you’re not competing in pro sports, there’s nothing wrong with using it. Someone once told me muscles are like makeup for men so then steroids are like botox. Not a big deal.

As we neared the end of our 10 minute TV interview for BET, I asked 50 if he used steroids, carefully explaining that, there’s nothing wrong with it because he’s not a pro athlete or a teenager. But the question sent 50 off into a rage (which should’ve been a sign that my guess was correct). He was angry that I had even asked and he explained to me, loudly, that he traveled with a nutritionist who was, he said, in the next room with the rest of his entourage so it was disrespectful to ask if he did steroids when he worked so hard on his diet. He said all this in a yelling tone while he stood up and walked off. Like,I asked the question and he stood up and yelled his answer as he stormed out of the interview. It was a chaotic moment. I said hey, if you say you’re not using steroids, fine. But about six months after our BET interview gone awry, I saw an article in the New York Times naming celebrities who had been caught in a steroids scandal. They included Mary J. Blige, Timbaland, and 50 Cent.

I said, well ain’t that a bitch. You lied to me. You got all mad at me for asking if you did steroids like you were the victim who was wronged when in fact I was right. My anger at him being angry at me for asking about steroids when he was absolutely using steroids, is why our third and final interview went completely off the rails.

One thing about interviewing big time recording artists is that in many cases, the label has to agree to the interviewer. And in many cases back then, a publicist might stay with a label for years. So if you somehow pissed off a big publicist at a big label then you might not get a chance to interview any of the stars at that label for a long time. If the publicists don’t trust you then you don’t get a chance to interview their artists. I’m not saying this led to softball interviews. There’s a level of hard questions that publicists understand is fair and then there’s questions they deem unfair. Sometimes they tell you in advance that the star does not want to talk about something. But sometimes they don’t tell you and you are kindof left to figure out for yourself where the line is. And if you can’t figure it out, then you might get in trouble.

At the same time, I was never one to let publicists bully me out of asking the questions that I felt needed to be asked. No singer needs to be asked about their recent divorce, but there are times throughout my career where I had questions that I felt needed to be asked even though they weren’t necessarily on the artist’s agenda. I may have had a bit of a reputation in this area. But it’s because I refused to let them scare me off of questions that I thought mattered.

So now it’s 2009 and I’m interviewing 50 for Fuse. It’s an hour-long TV interview in front of multiple cameras. He came to the studio with many label execs in tow, like ten white people in business casual. They were all standing silently in the wings as we talked. After about 55 fantastic minutes of our hour-long talk a little devil popped up on my shoulder. As 50 was talking the little devil said to me, “You gonna ask him about steroids or are you gonna be a pussy?” I tried to ignore him. A little angel popped up on my other shoulder. “That question would not be appropriate.” The devil said, “Are you actually scared to ask the question? What the fuck is wrong with you?” The angel started to talk but the devil punched him in the face. He said to me, “You’re gonna let some rapper scare you? Are you kidding me?” A lot of internal conversation while 50 was talking. By the time he’d finished answering, my internal debate was over. I couldn’t wimp out. My inner voice would have shamed me for the rest of the week.

“So,” I began, “the last time we talked you said you didn’t do steroids but then there was an article in the New York Times that named the doctor who prescribes your steroids.” I could hear the rustling and murmuring from the label execs in the wings. “But you’re not a professional athlete so it’s totally fine for you to do steroids. So why don’t you just admit that you do steroids?”

50 took a pause, looked at me and said, “A lot of rappers say you’re an asshole.” Then he spat out a loud, condescending laugh. That hit like a bullet to the chest. I felt his power as a bully—now I had to start thinking, wait, rappers are out here saying I’m an asshole? I started mentally calculating which rappers might be saying that. It was the perfect thing to make my mind start racing so it seemed like forever between him saying that and then laughing and then finishing his thought. “I just say you ask fucked up questions.” I don’t remember much after that. My producer was pretty mad that I’d asked that. I know the label execs were mad. I had violated the dance we were supposed to do. I had not been told you can’t ask about steroids but everyone would’ve assumed that I would know better than to ask about steroids. But, in retrospect, I’m glad I did it because whatever castigation I got from my boss that day is nothing compared to how my inner voice would have beaten me up if I’d backed away from the question because I was scared.

I have never talked to 50 Cent since then but if we did another interview I would probably start with, so… you still doing steroids?

Hahaha

This is a book. Great job!