The 2nd Worst Interview Situation I Ever Had AKA the time Mary J. Blige Was Really, Really Rude To Me

I'm still hurt, Mary. What did I do to deserve this???

This is the 2nd worst interview situation I’ve ever had. So it’s the worst except for the time that Suge Knight practically kidnapped me and threatened to beat me up and I thought I was going to die. I’ll tell you about that another day. This is a story about Mary J. Blige.

In 1994 when she was as hot as fish grease with her legendary sophomore album “My Life,” the New York Times arranged for me to spend a day with her. The concept was for us to go back to the Schlobaum projects where she grew up. Successful singer goes back home.

The lead single on that album was “Be Happy” but deep down, Mary was not happy. That was the summer that she got into a fight with dream hampton when dream was writing about her for Vibe. I got it even worse.

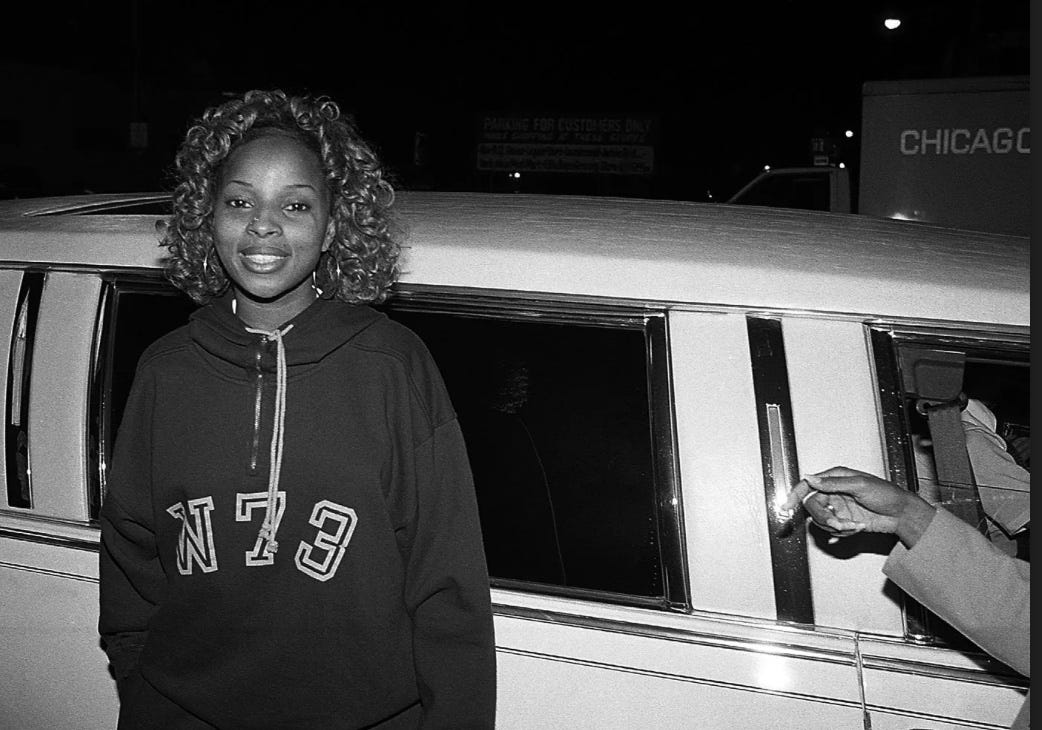

Mary was still new to the industry then and not very trusting or open. And she was quick tempered. It would be a long day. We met in Manhattan and got in a limo with a bunch of people from the label. She was quiet and shy so when I tried to ask her a few questions she brushed them off. She answered one question by snapping “What do you think?” After another question she muttered, “You’re so stupid.” Then she turned away and started talking to her friend, cutting me out of her attention. So I laid back and stayed quiet, trying to give her time to warm up.

The limo ride up to Schlobaum was her talking to her friend and me staying quiet but that was fine. I was just observing. We got to the projects and went to see her mom and within moments the whole pj’s knew she was there so the halls were filled with excited people wanting to see her. She said a few hellos and then kinda rushed out and down the stairs and got back in the limo with like 10 friends. I could see right away that this would be a good moment for the story. Mary in a limo partying with her old friends. That could be a great opening scene.

She and I had barely spoken the whole day but when I went to climb into the limo along with her peeps she pointed at me and said aggressively you can’t come in. Oh. Ok. So I stood outside for 30 minutes while she and the crew had big fun drinking and smoking and laughing. I knew a great scene for my story was happening without me but I had to chill.

When the little party finally ended her crew filed out of the car and the label folks piled in. I got in last. When I sat down she said to me “Don’t speak to me for the rest of the day.” We had barely spoken but ok. Why was she so mad at me? I have no idea. I think she took one look at me and decided I wasn’t her kindof person and wanted nothing to do with me. Later on, Andre Harrell, the head of her label Uptown, said she probably was like here’s a clean cut preppy negro from the hoity toity New York Times and I don’t like him because I’m real one from the hood. Maybe, but dream hampton is definitely a real one—from the hood of the East Side of Detroit—and Mary also had words with her.

Her aggressive demand arrested the whole vibe in the limo. No one spoke for the whole 45-minute ride back to Manhattan. And when we got to Manhattan, to like 55th street and 10th avenue, kindof the edge of Manhattan, she said “Get out here.” We weren’t really near anything, it wasn’t like a convenient place to get out. It was a sketchy area that wasn’t really near the subway. She might as well have made me get out with the car still moving.

Anyway, when the label heard what had happened they were mortified and they were scared that I’d write a horrible article about her. The head of her label, Uptown, was Andre Harrell. He was a friend. He urged me to be understanding of Mary. He said, Mary was a victim of her upbringing. Harrell, also, grew up in the hood. “You can’t get rid of all that pain and all those horrors overnight,” he said. “She lacks the self-confidence of someone of her stature because she grew up with someone telling her, ‘You ain’t nothing and you’re never going to be anything.’ In the end she turned out to be just the opposite: something very special but she’s still a victim because she doesn’t know it yet.”

That made sense to me. But I was never going to write a negative article about her. I had to pivot and figure out how to write the story because I never got to interview her—it shifted from a profile to a discussion of the image-making machine around her.

But in a situation like that, the journalist has got to put their personal feelings aside. Don’t make it about she was rude to me. It still has to be a story about her that speaks to who the star is and what the fans want to know about her. The journalist is, in many ways, a conduit. You can’t take the way the artist treats you personally. While you’re writing the story you have to forget about how the artist treated you. You can’t be petty. She was a very important artist and it was my job to put her in context in the culture, not to settle a score because she was rude to me. Most of this story I’ve written here was not reflected in the story I wrote for the Times.

But I never forgot.